THE ART CONNOISSEUR & MAN THAT SHAPED BRITISH PHILANTHROPY

It heads to auction for first time in 100 years directly from his descendants

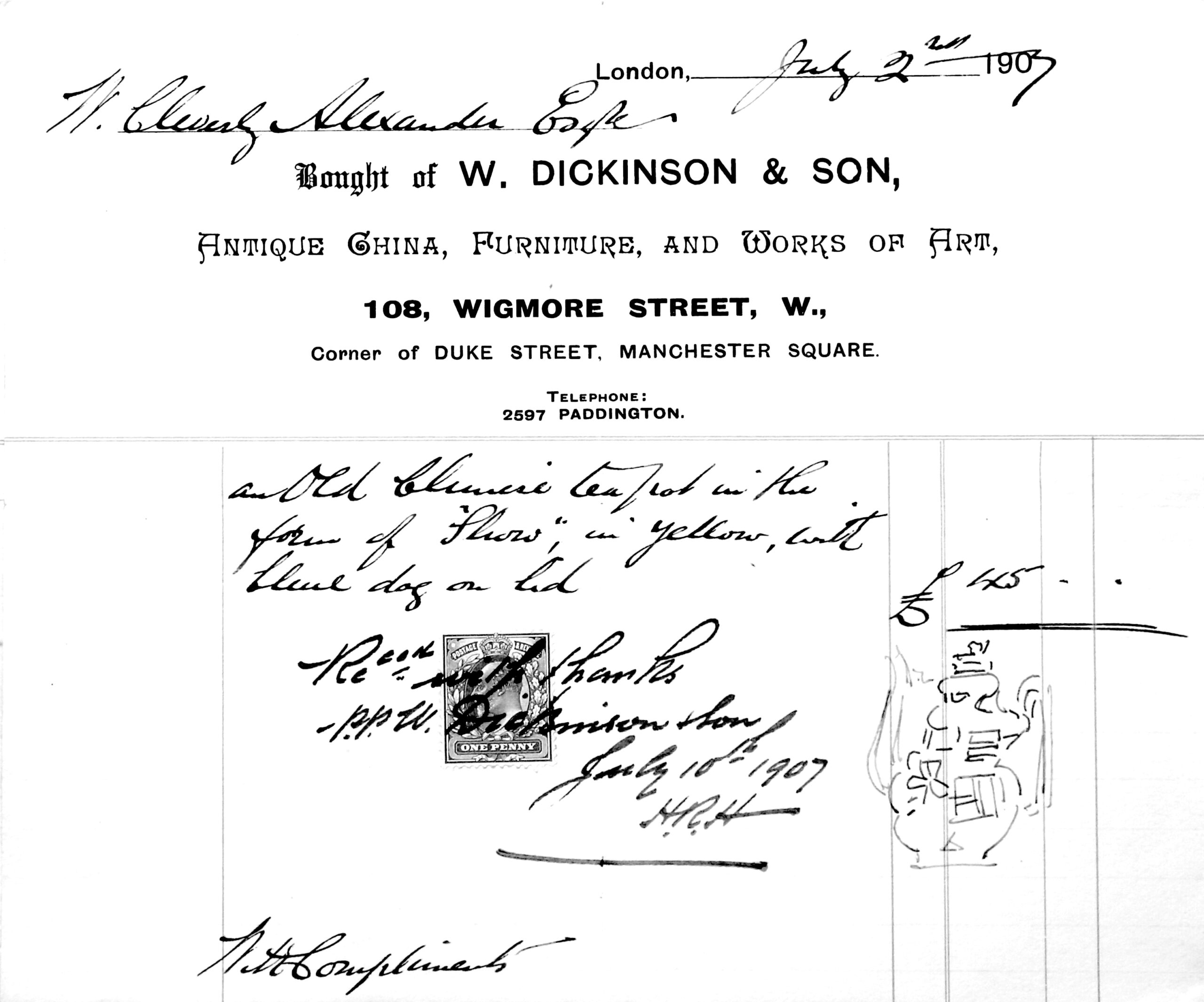

UK. MARCH 2025. Woolley & Wallis is excited to present a rare Chinese wine ewer from the private collection of one of Britain’s most knowledgeable art connoisseurs and philanthropists, William Cleverley Alexander (1840-1916). The wine ewer from the Kangxi period (1662-1722) has remained in the family collection since it was purchased in 1907 and will be offered for auction alongside a vase from the same period, for the first time in over 100 years. Known for his curatorial skills Alexander chose quality over quantity for his collection, with each piece being thoroughly researched before being purchased. His meticulous documentation of the pieces was also key and each piece comes with its original invoice and drawing.

Woolley & Wallis is especially thrilled to be able to offer the ewer, not just because of the esteemed pedigree of the works in the Alexander collection, but also because the auction house broke the million-pound barrier for a Chinese work in a UK regional auction house 20 years ago, when it sold a Chinese Yuan dynasty vase from the Alexander collection for £3 million against an estimate of £200,000-£300,00 in July 2015.

Commenting on this exciting offering in Woolley & Wallis Fine Asian Art sale on May 20, 2025 John Axford, Asian Art Specialist and Chairman of Woolley & Wallis, said: “It is an honour to be entrusted to sell this fine and rare piece. It epitomises the keen eye for outstanding craftsmanship and quality of materials that William Cleverley Alexander had, as well as demonstrating his passion for works from this period. There is a demand for the highest quality works with such stunning provenance, careful curation and preservation and we therefore anticipate interest from around the world.”

The original 1907 invoice for the rare Kangxi yellow-glazed wine ewer fashioned in the shape of the Chinese characters Fu Lu Shou

His collection was housed between the family homes of Aubrey House in Kensington and his country house, Heathfield Park in Sussex. The wine ewer is from the Chinese Kangxi period (1662-1722), which was a period of recovery following the collapse of the Ming dynasty. This era of renewed stability instigated a surge in artistic creativity, predominantly in ceramics. This, combined with groundbreaking technical advancements resulted in ceramics from the Kangxi period being regarded as some of the most exquisite ever produced.

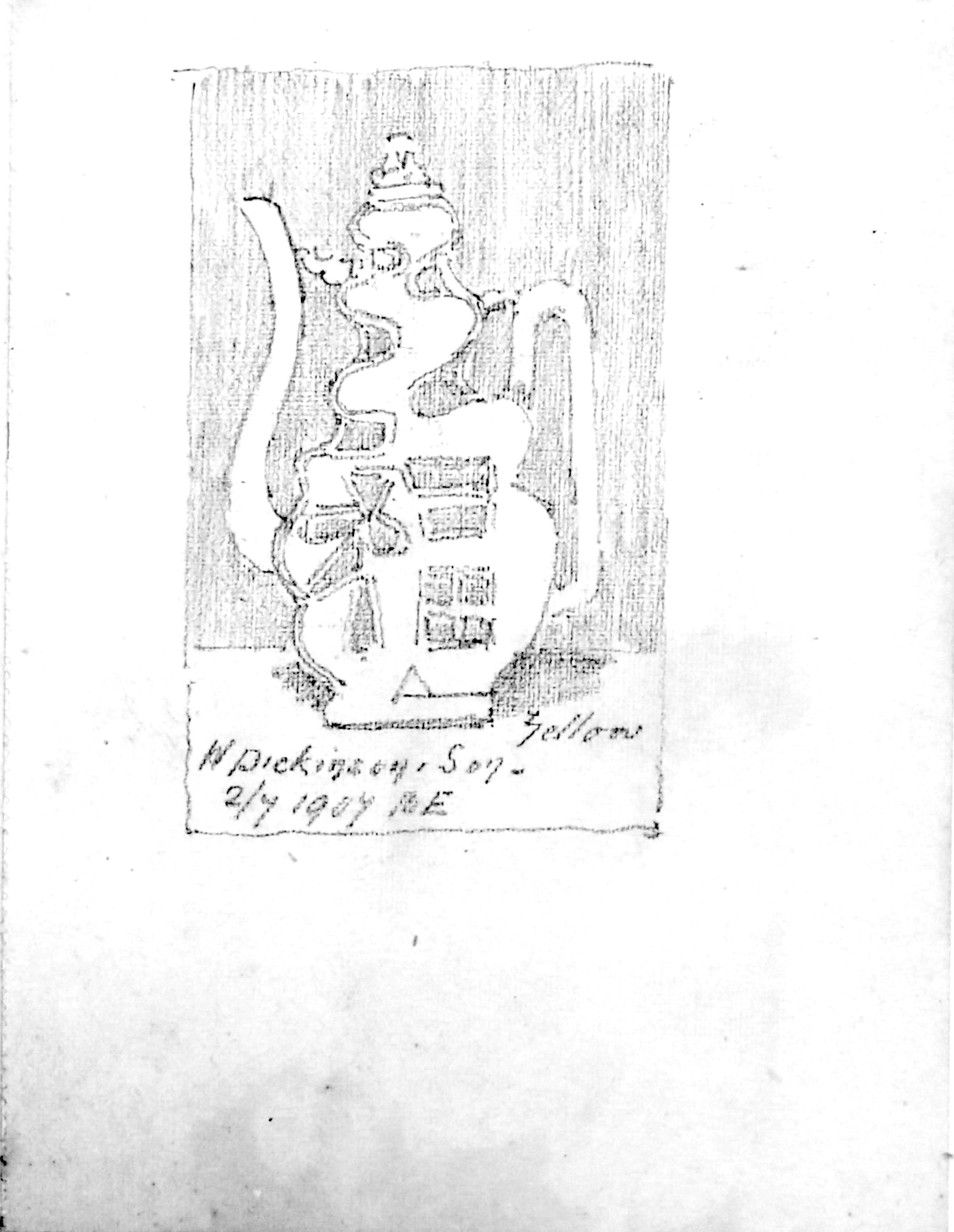

The vibrant rare Kangxi yellow-glazed wine ewer is fashioned in the shape of the Chinese characters Fu Lu Shou 福祿壽 which translates as good fortune (Fu), prosperity (Lu) and longevity (Shou), representing the three key aspects of a good life in Chinese culture. This ewer therefore is a symbol of positivity. There were various uses for wine ewers of this period, from ritualistic or ceremonial use, to funerary versions (where they were created to literally ‘toast’ the dead) and some for more practical usage, such as birthday celebrations. China’s wine industry has a long history dating back to circa 1000 BC, when rice wines were first made. During the Kangxi Emperor’s reign Chinese people drank Huiquan Wine, a yellow wine made from glutinous rice and spring water. It was from the Jiangsu province and was popular with the affluent. The wine was considered high-quality and therefore classed as a perfect gift, as well as exceptional enough to be an Imperial wine (consumed by the Royal court). Also popular was qióng jiāng yù yè, which translates from Chinese to ‘jade-like wine’ and held in such esteem that it was mentioned in the Complete Tang Poems, a highly-respected 18th century collection of poems compiled during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor.

John Axford tells us: “Ceramic wares modelled in the form of characters like the present wine ewer were a remarkable innovation of the Kangxi period. This ewer is a particularly decorative example, with an unusually long neck and moulded as the combined characters of Fu and Shou. It is applied with a loop handle and a slender, tapering spout, with a charming blue glazed Buddhist lion finial which contrasts strikingly with the yellow.” It carries an estimate of £4,000-£6,000.

The wine ewer is being offered alongside a rare underglaze meiping (vase) deco

About William Cleverley Alexander (1840-1916)

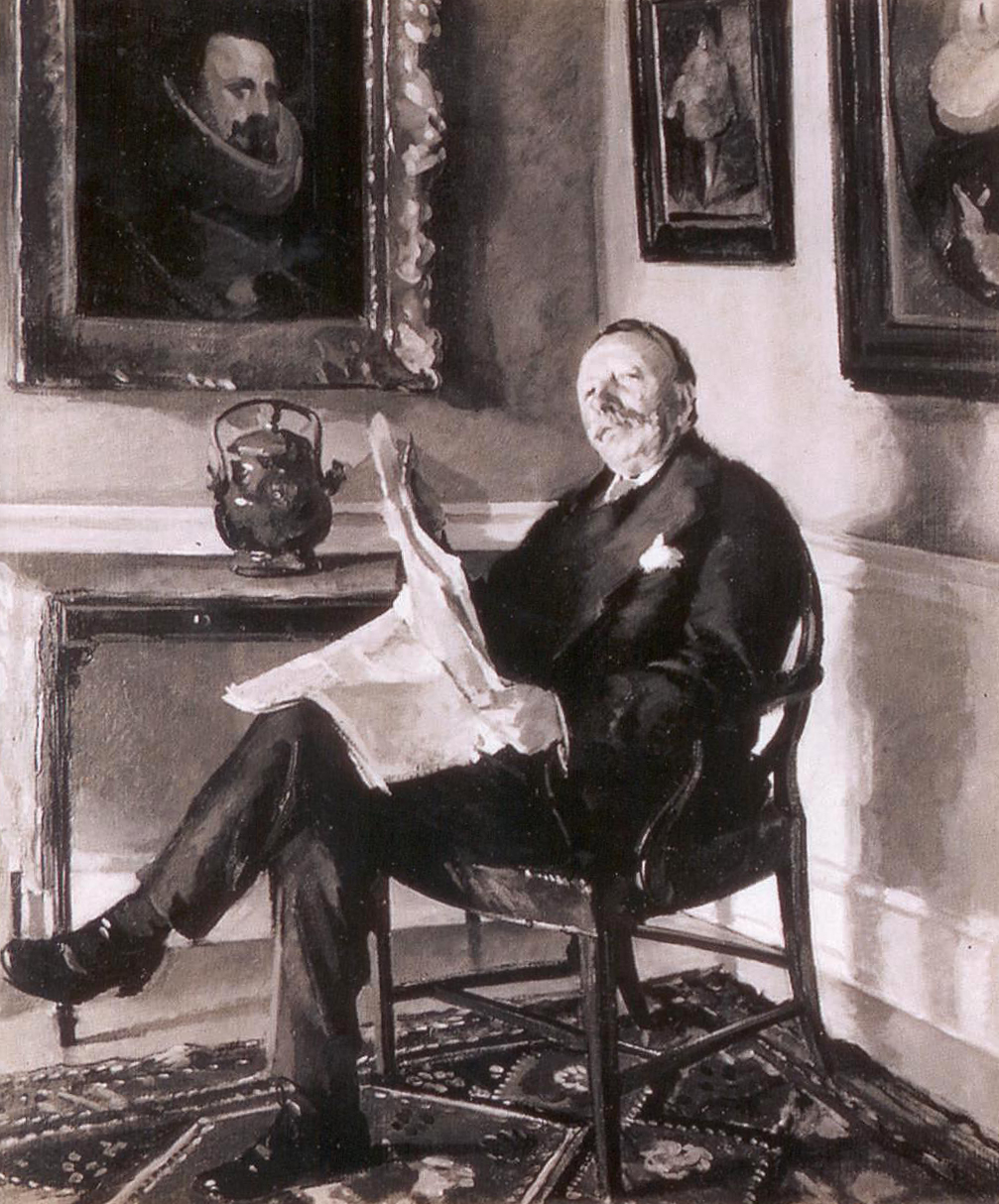

William Cleverley Alexander (1840-1916) was a British banker, art collector and patron, known for his keen interest in Asian and European art. Born into a wealthy family, he used his financial resources to amass an impressive collection of Asian art.

His collection reflected both his refined taste and the Victorian fascination with Chinese and Japanese aesthetics. His contributions helped popularize Asian art in Britain and his patronage supported emerging artists of the time. One such artist was the UK-based American painter James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). Alexander commissioned several works by the artist, including portraits of his three daughters: Harmony in Grey and Green: Miss Cicely Alexander; Miss May Alexander and Portrait of Miss Grace Alexander.

Drawing of the rare Kangxi yellow-glazed wine ewer fashioned in the shape of the Chinese characters Fu Lu Shou

Alexander was a member of the Burlington Fine Arts Club and a founding member of the National Art Collections Fund. He liked to ‘share’ his collection with the wider public and often loaned his works to multiple museums.

The British painter, art critic and founding member of the Contemporary Art Society, Roger Fry (1866-1934) said: “Alexander was one of the most important figures in the world of art.” He further complimented him in an obituary in the Burlington Magazine in 1916: “He was the most unpretentious of men. He seemed incapable of regarding his wealth or the quite remarkable taste which guided its expenditure as any claim to distinction. In contradistinction to so many collectors who use their possessions to make status, he seemed almost to apologize for his good taste and his good fortune.”1.