Stephen left school at 15 to take up a position in an insurance company. Thrilled by the City of London but bored by insurance, he took up employment in menswear sales to make the most of the Swinging Sixties, whilst sharing a flat in West Croydon with two of his brothers. When they went their separate ways, he rejoined his parents who had moved up to a small village, called King Sutton, near Banbury Town, and it was here that his artistic life began when he enrolled in a painting evening class run at the local art school.

There he discovered that he had artistic talent and, encouraged by his tutor, he enrolled onto the pre-diploma course at Banbury School of Art. On completion, he was accepted into fine art diploma course at Leicester Polytechnic where he was awarded a First-Class Honours Degree in Fine Art. Subsequently, he won a Higher Diploma place in the newly created Experimental Department at the Slade School of Art and Design, University College London.

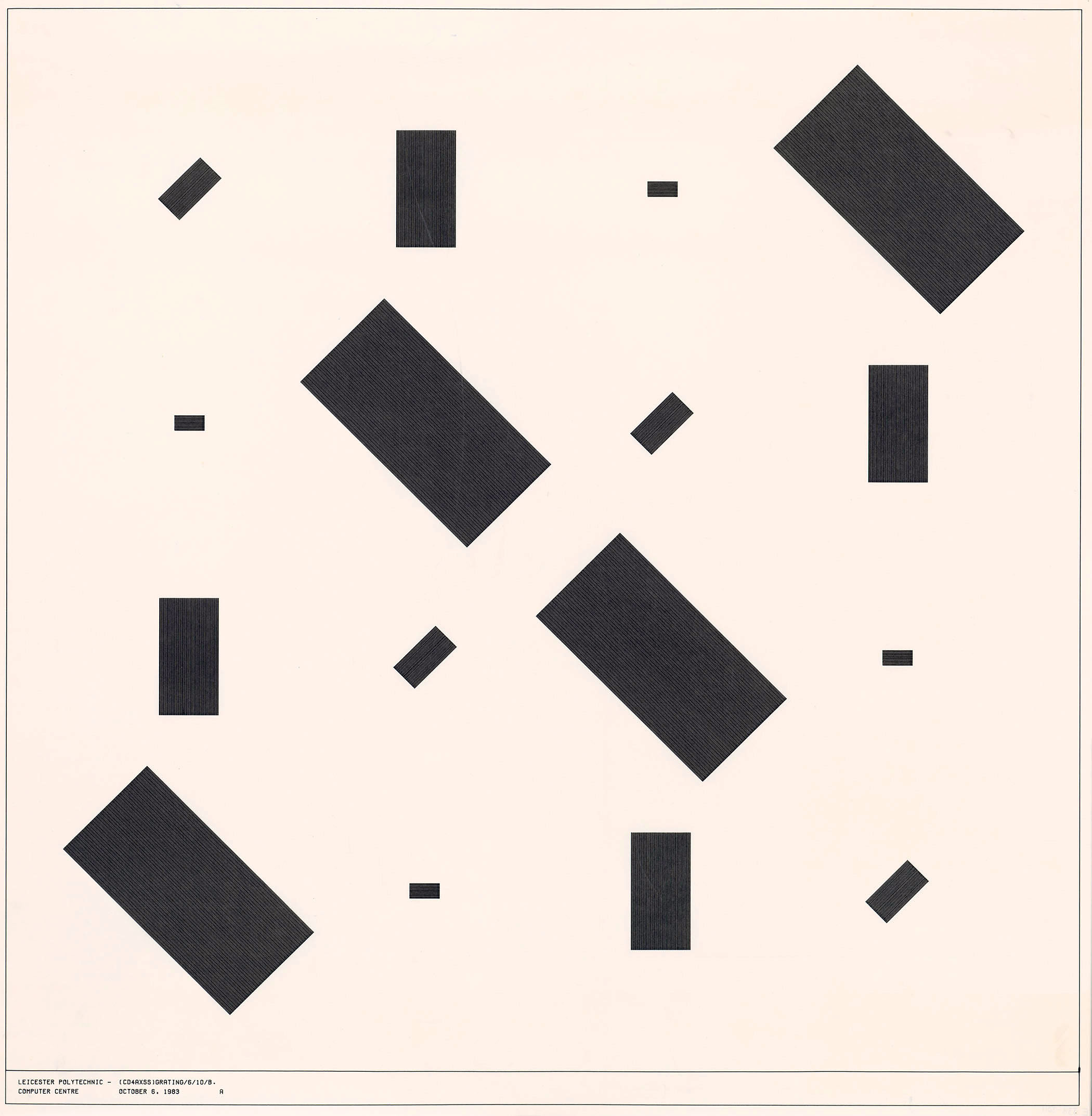

While at the Slade, he started making computer art and on completing his higher diploma he was awarded a PhD scholarship back at Leicester Polytechnic in the Computer Science Department. Here his career took a new turn, and he spent the next 18 years teaching and conducting research on human-computer interaction before returning to the art school as Associate Dean Research, School of Art and Design, Derby University. Following research leadership positions at Central Saint Martins and Chelsea College of Art, where he is now an Emeritus Professor. Throughout his career, Stephen has maintained his creative practice part-time and full-time since 2010. He has exhibited nationally and internationally, and his work is held in public and private collections.

What’s your artistic background?

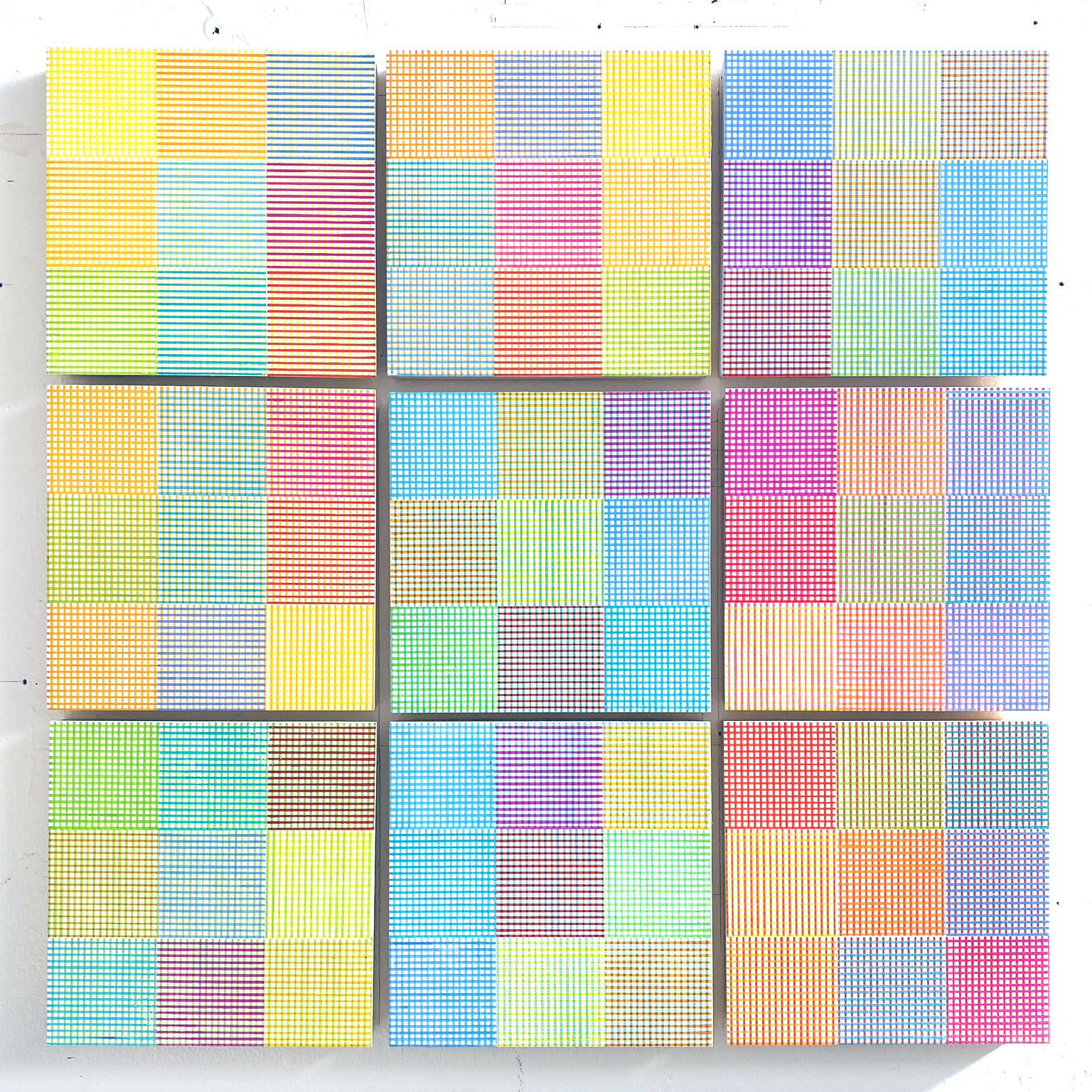

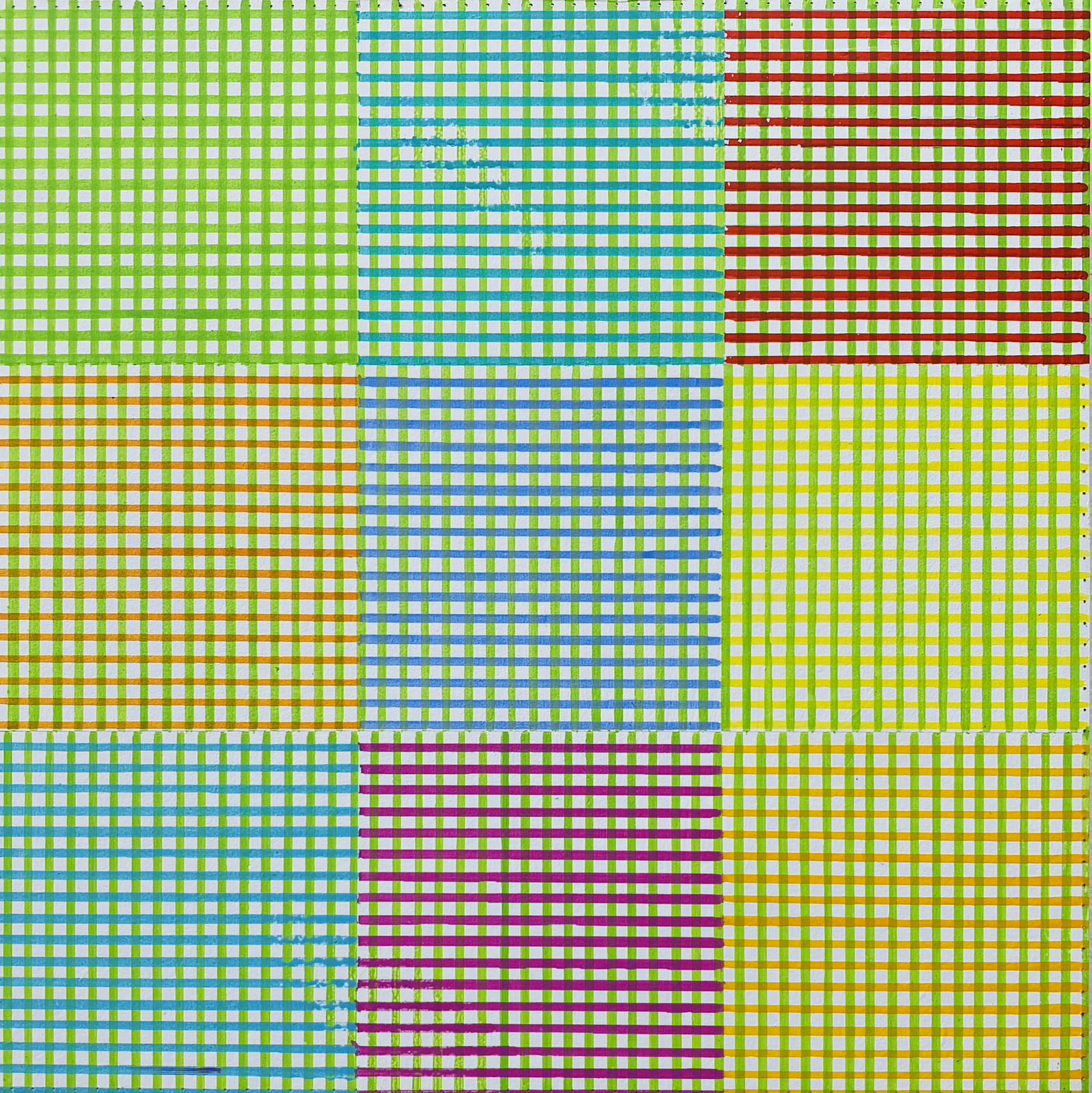

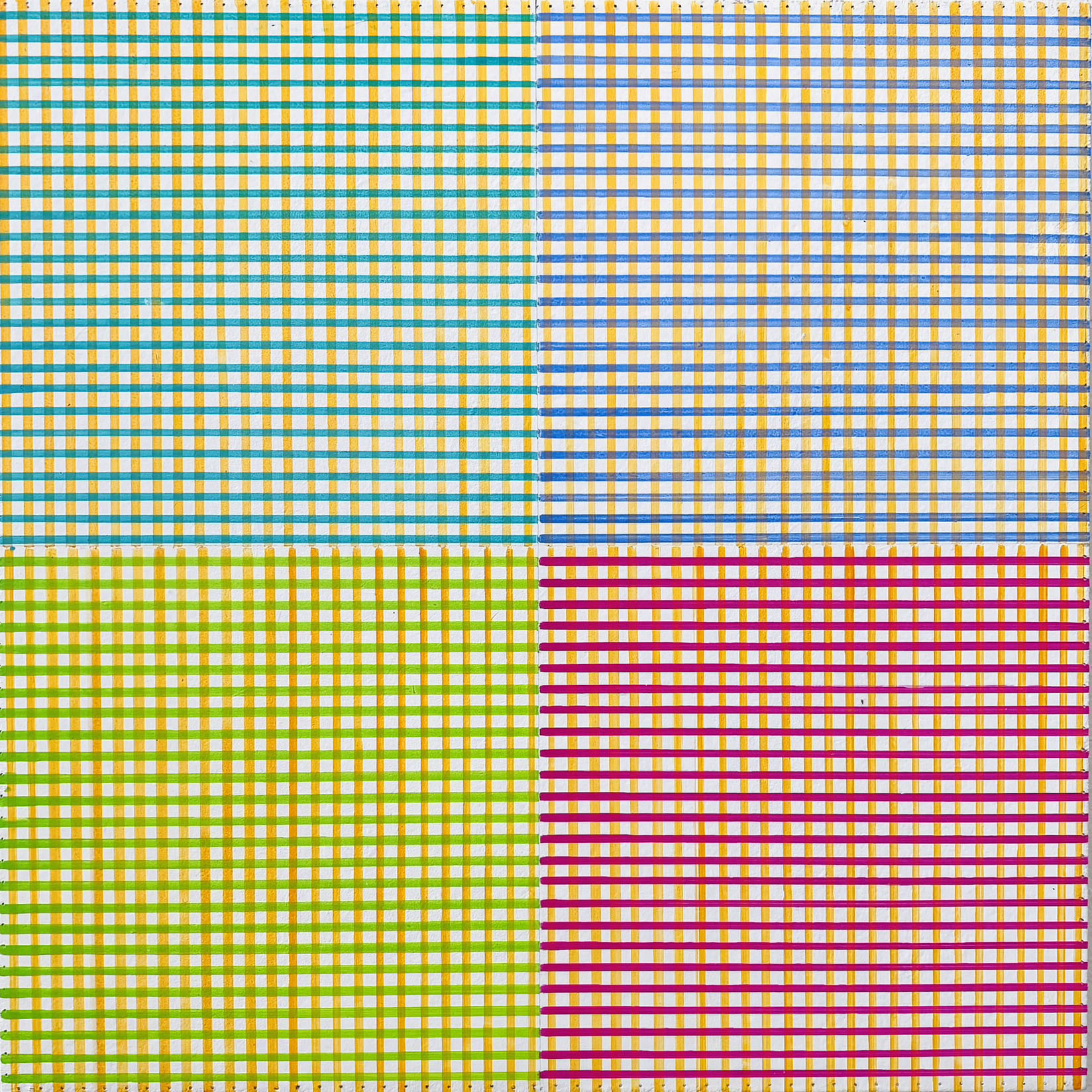

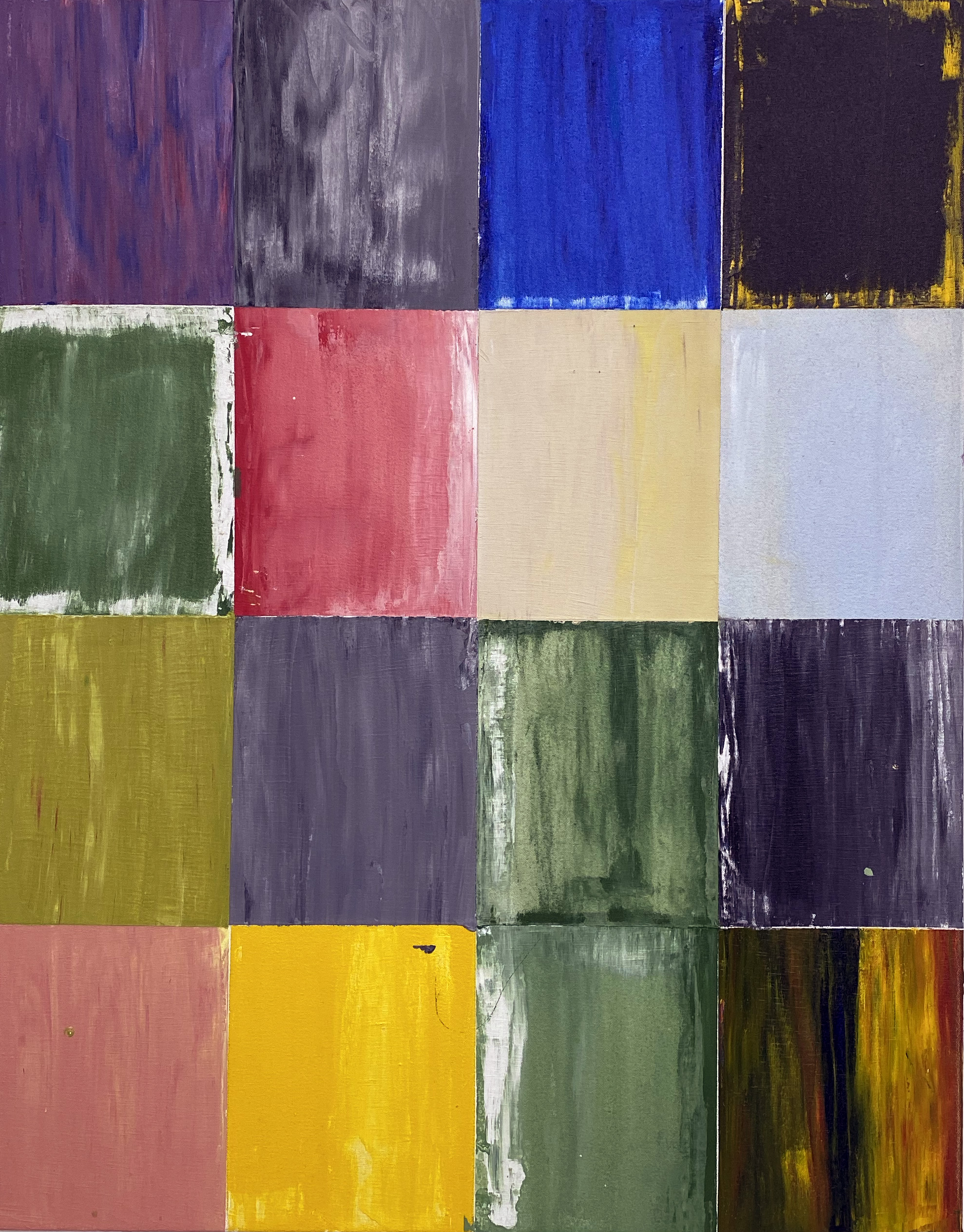

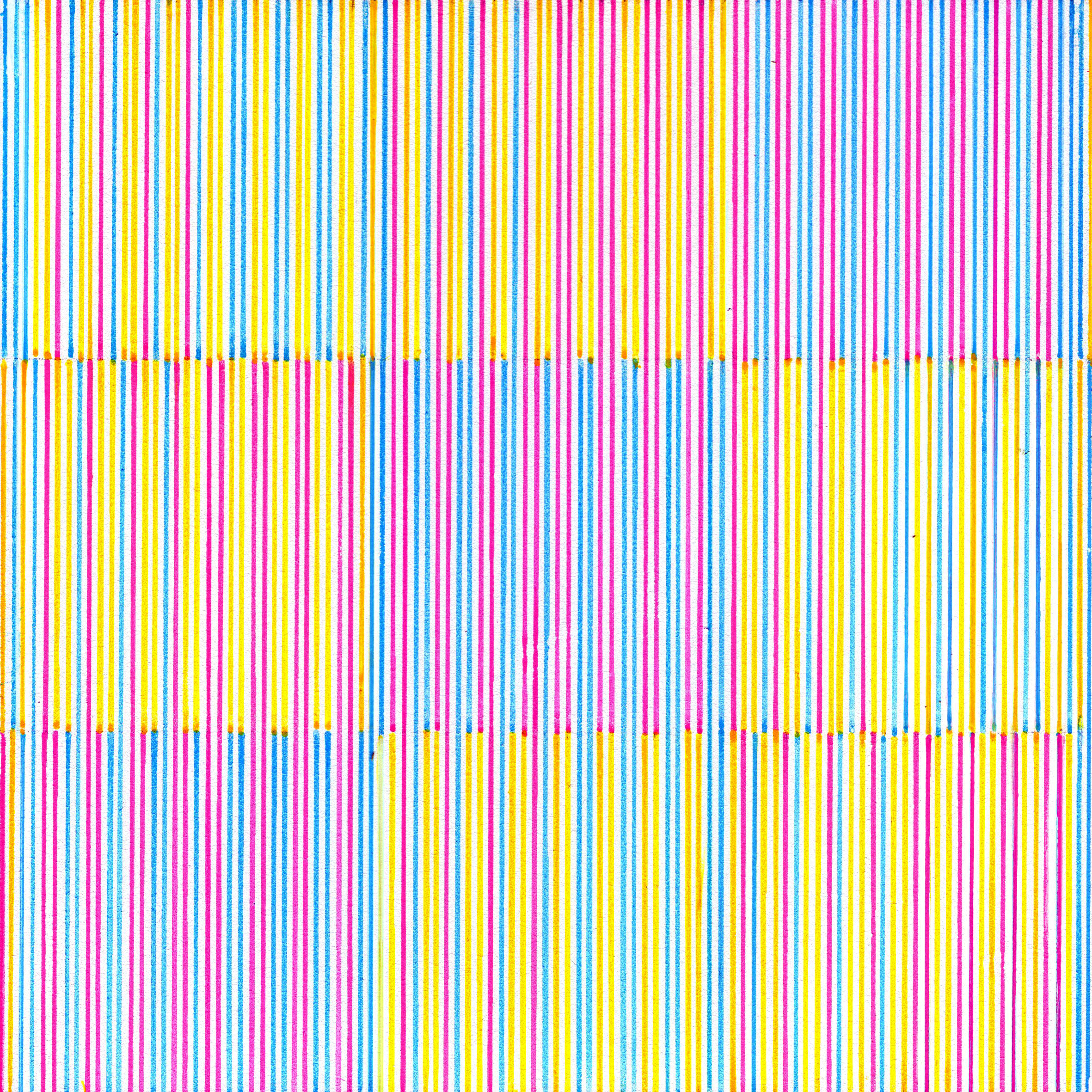

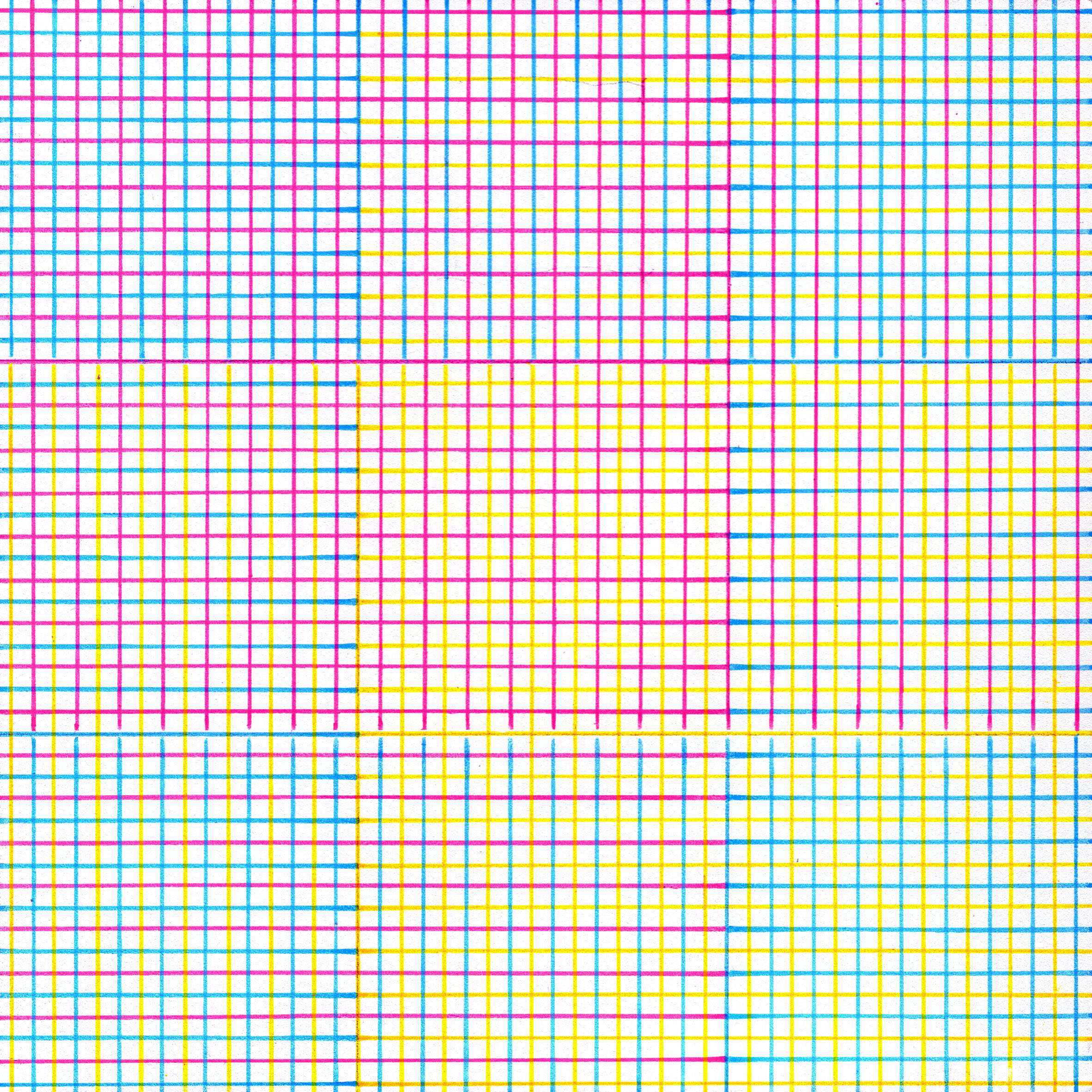

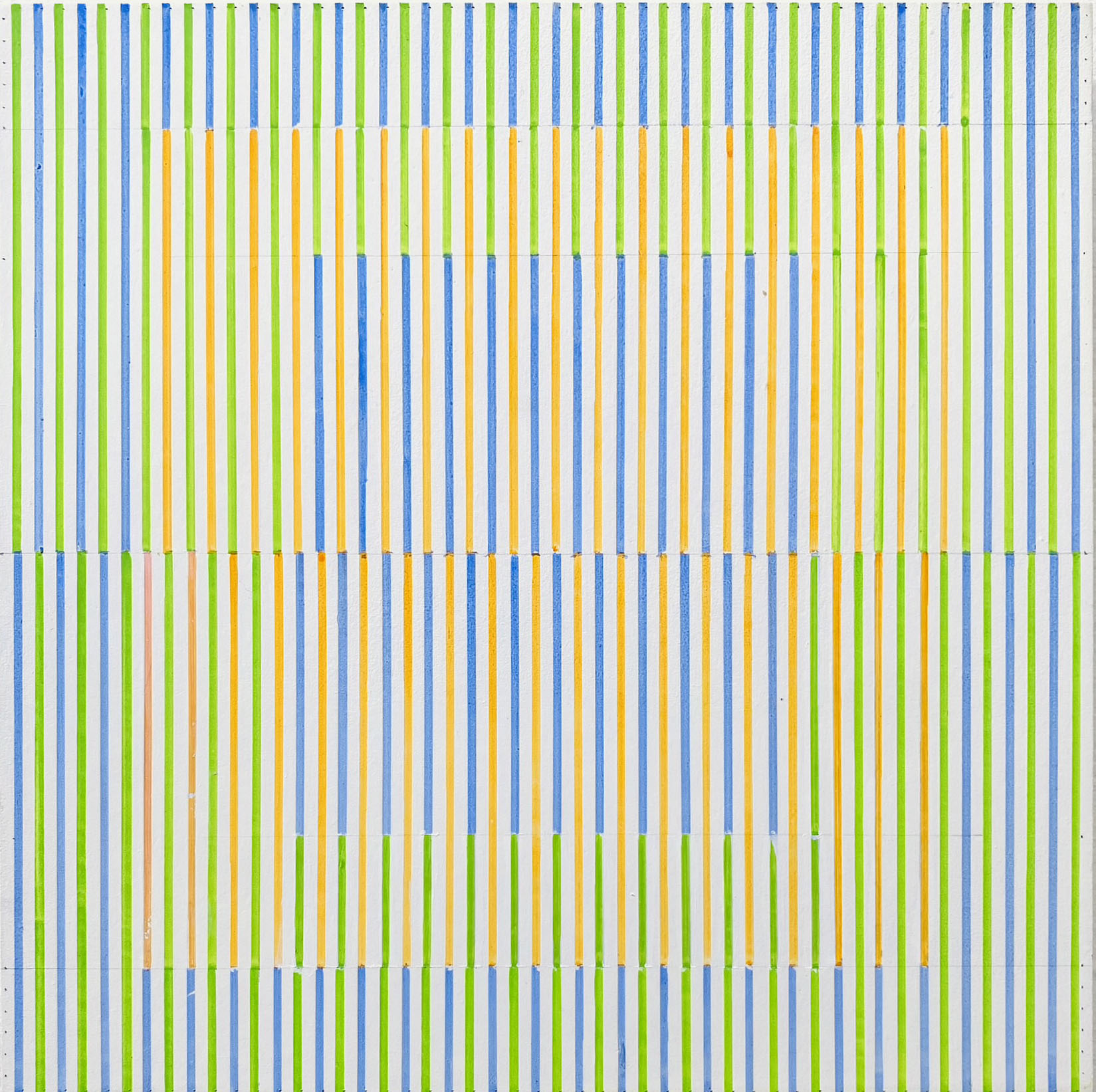

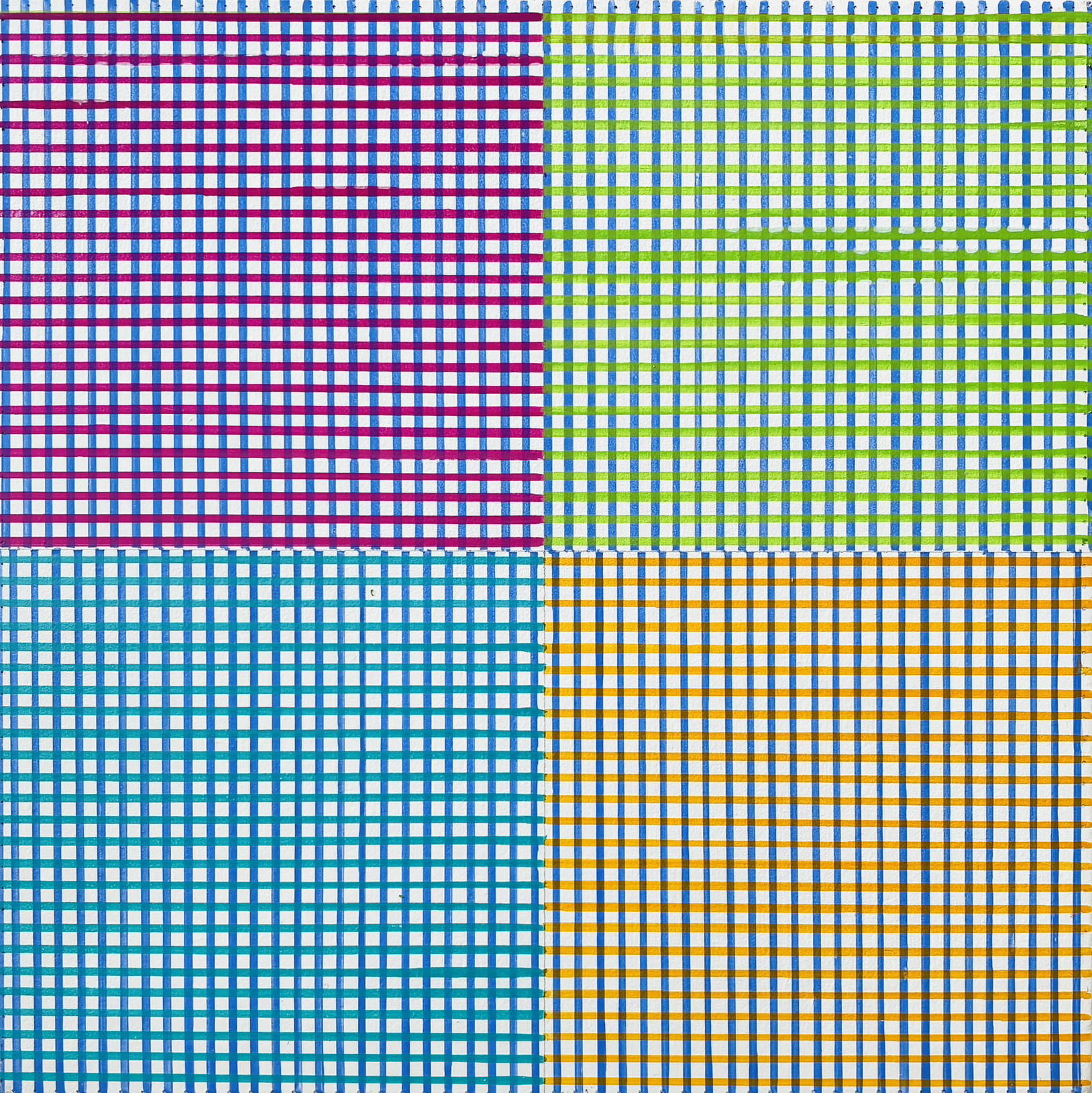

Like many artists, I started as a painter but upon entering art school in Leicester I found myself amongst a group of radical teachers influenced in their teaching methods by the Bauhaus and experimental in their practices. I quickly gravitated toward their ways of thinking and doing, creating kinetic pieces using natural phenomena as image making media, such as light and water. This experimental approach to art making aligned with a new initiative at the Slade School of Fine Art, as they had just established the Experimental Department, where I joined a like-minded group of slightly off-the-wall students. The Slade is a school within University College London and consequently I was able to use its mainframe computer. So, I taught myself how to program and shifted from natural to symbolic systems of image making. I stopped making computer art around 1984 because I get immense pleasure from the act of image making and the immersive, meditative, slow thinking that manual drawing and painting allows. However, I do not think my fundamental attitude to practice has changed. In my abstract practice, I neither compose nor construct; rather I formulate systems of parameters and constraints and work through the possibilities they allow.

What’s integral to the work of an artist?

Many things are integral to artistic work, but I want to highlight time for and continuity of practice as key. There is this romantic idea of the artist as a creative genius who wanders around with her head in the clouds awaiting inspiration to strike before picking up pen and paper to dash of a masterpiece. However, Thomas Edison was correct that success is 10 percent inspiration and 90 percent perspiration. To get anywhere interesting, I need to put the hours in without extended absences from my studio. And this is not just about what is needed to realize a promising line of inquiry: continuity of practice is also critical to getting through those patches when your work is not going anywhere.

What role does the artist have in society?

This is a big question to which the answer is manifold, depending on your artistic standpoint. Yes, art decorates, entertains, and brings beauty, pleasure, enjoyment, and escape from the trouble and stress of modern life. However, the role of art is not only to satisfy our aesthetic, emotional, leisure and domestic needs but to convey knowledge, to challenge what we believe and how we see the world and to help make sense of it. In short, I do not think art would have the place it has in culture and in our hearts if it was only about aesthetic pleasure and emotion; art is also cognitive – a source of learning and knowledge. At least for me it is as I seek out art that I can learn from, and which stimulates and inspires what I do next. I like to think that I am not alone in this.

What art do you most identify with?

I am an eclectic and voracious art goer and appreciate and identify with a wide range of art styles and periods. Nevertheless, thinking about the art that influences me most I would have to say it is non-compositional, non-constructive abstract art; art that draws on rules, processes, and abstract systems as image making devices, such as seen in minimalist and computer, mathematical and systems art.

What themes do you pursue?

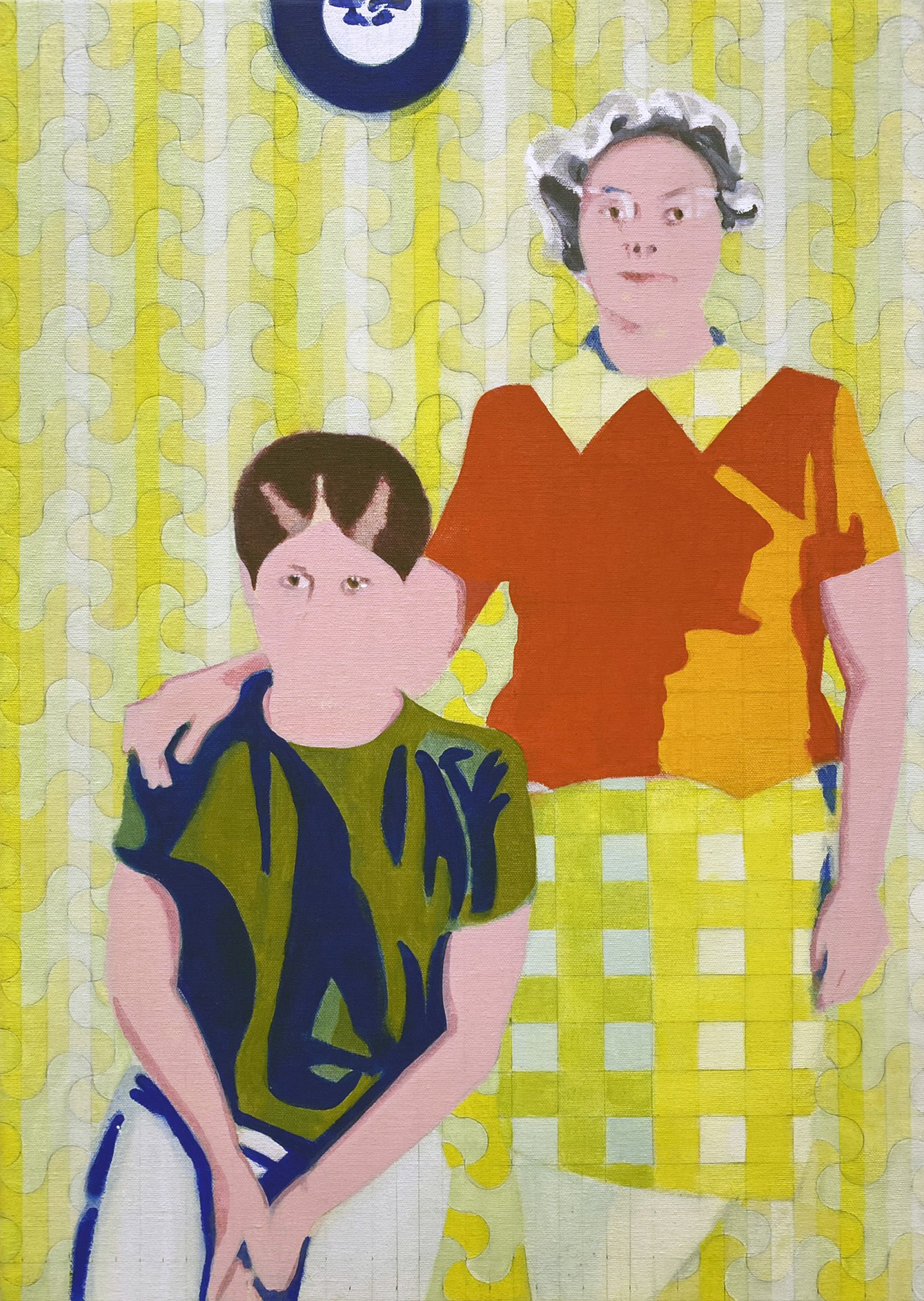

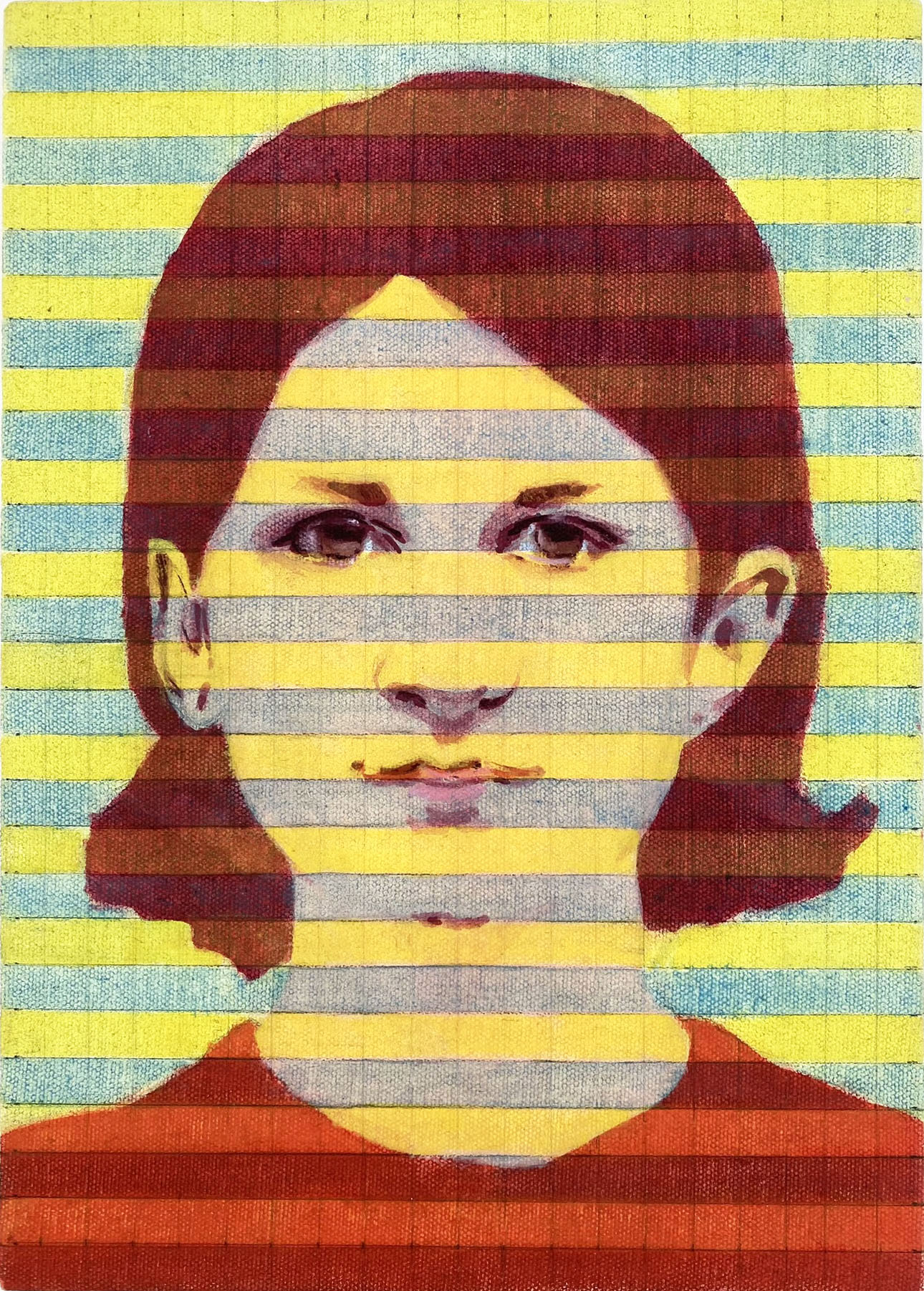

Typically, I like to work in both abstract and issue-based modes. What we usually think of as themes or subjects do not figure in my abstract work, but if we think of a theme as unifying or dominant idea, my abstract work’s theme is new image orders. Recent themes in my issue-based figurative work include photographic objectification, global warming, Covid 19 and the Ukraine War.

What’s your favourite art work?

Honestly and perhaps because I am an artist, I cannot nominate a favourite artwork: artists tend to favour any art that feeds their practice. Still, thinking about some of the galleries that surround my central London home: at the Courtauld I head for the Cezannes, at the National Gallery the Titians, Vermeers and Constables, at Tate Modern the Gerhard Richters and Agnes Martins, at Tate Britain the Pasmores, and at the Dulwich Picture Gallery the Rembrandt’s and Velásquezs. Nominating favourites is easy but nominating a favorite is impossible.

Describe a real-life situation that inspired you?

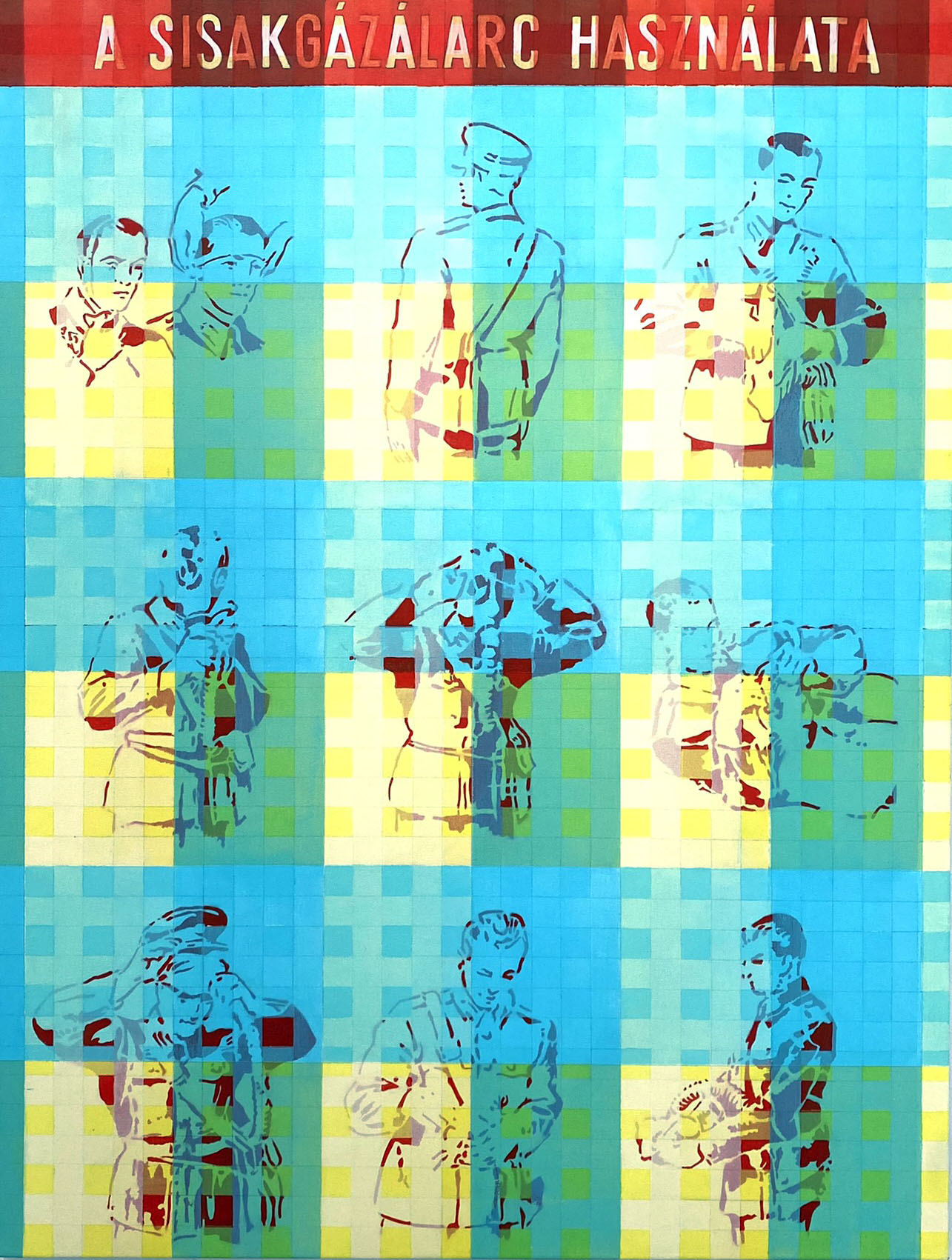

In 2010 I visited a bunker in Budapest built during the second world war and used during the Russian cold war presence in Hungary as a training and command centre for post-nuclear war survival. On entering this modern ‘Mary Celeste’, it seemed as if the occupants had been plucked out one day, never to return, because, after more than twenty years, it remained fully furnished and populated with all the paraphernalia needed for ‘survival’ after nuclear attack such as desks, chairs, maps, shovels for clearing ash, telephones, tee shirts, Wellington boots, medical supplies, instructional posters, etc. This experience stimulated an on-going series of works and exhibitions.

What jobs have you done other than being an artist?

As explained above, my artistic life has been coupled with the life of an academic, so I have not had to rely on sales to make a living.

Why art?

For all the reasons that I mentioned earlier and above all because art constantly reminds us that there are no limits to human creativity: just when you think you have seen all there is to see of what it can tell us along comes art that surprises and forces us revise our understanding of art, life and the world Life would not only be very impoverished without past and contemporary art of all complexions; it would be more frightening and less hopeful. Art reminds us that we can be and do better.

CIS:E.338-2011

What is an artistic outlook on life?

Overall, to be an artist is to be ambitious, positive, optimistic, resilient, self-believing and, paradoxically, satisfied with our achievements. Few artists are content with repeating themselves and most want to do something different every time they start a new creative journey and not just personally different; they want to make a difference to art in general. However, such ambition is hard to achieve, and disappointment is a constant companion. If you lack the above attributes, you are unlikely to last the course or be satisfied with what you achieve, which is unlikely to match your ambition.

What memorable responses have you had to your work?

In 2019, I completed as series of painting that combined the Antarctic past, as recorded in photographs of the early twentieth century British Antarctic Expeditions, with a possible Antarctic future, as imagined in photographs of the Andes, which are believed to be geologically like the Antarctic bed. Having explained to one exhibition visitor the visual idea behind the work, he observed that he had not registered the combined imagery but was struck by the sense of loss that the images conveyed. This was memorable and surprising because whilst I had been focused on the artistic potential of combining imagery, I was reminded of why I had chosen the issue in the first place.

What food, drink, song inspires you?

Lucca is another beautiful Italian city that I have visited many times that is blessed with the wonderful, tiny Pizzeria da Felice that sells pizza by slice and weight. It was there that I first encountered a kind of flatbread that is called La Cecina or Torto da Ceci in Tuscany. All you need to make it is chickpea flour, water, olive oil and salt, which makes it sound too simple to be anything special but special it is as is often the case with simple things.

Is the artistic life lonely? What do you do to counteract it?

Whilst it is true that most of my time is spent alone in my studio, I have never experienced loneliness. My studio is in a complex, so I am surrounded by a community of artists, and I am blessed with a stable and loving family. In fact, I enjoy the solitude and silence of my studio and the immersive and meditative nature of my practice.

What do you dislike about the art world?

The art world is dominated by the art market and the public museums and galleries and there is much about both to dislike. However, what I really find abhorrent in the contemporary art market is the rise of the so-called Vanity Art Gallery sector. These galleries approach and flatter artists with the offer of participation in a group exhibition in London, Rome, Milan, Berlin, etc. However, participation usually comes with a significant entry fee and shipping costs to and from the exhibition venue. Typically, these galleries load their costs on inexperienced and young artists, seduced by the galleries’ overtures and the promise of visibility, who rarely gain a return on their investment.

What do you dislike about your work?

Preparing canvases and panels is not something I particularly enjoy. I like to select canvas and stretchers, and to stretch my canvas and, at present, I am painting on 8” x 8” panels that I make and prepare myself. This is hard, time consuming and dirty work that often becomes necessary when I am champing at the bit to get a new series going or completed. It is not the labour I dislike; it is the disruption of practice. However, I try to use the time positively to reflect on past and present work and to conceive new work.

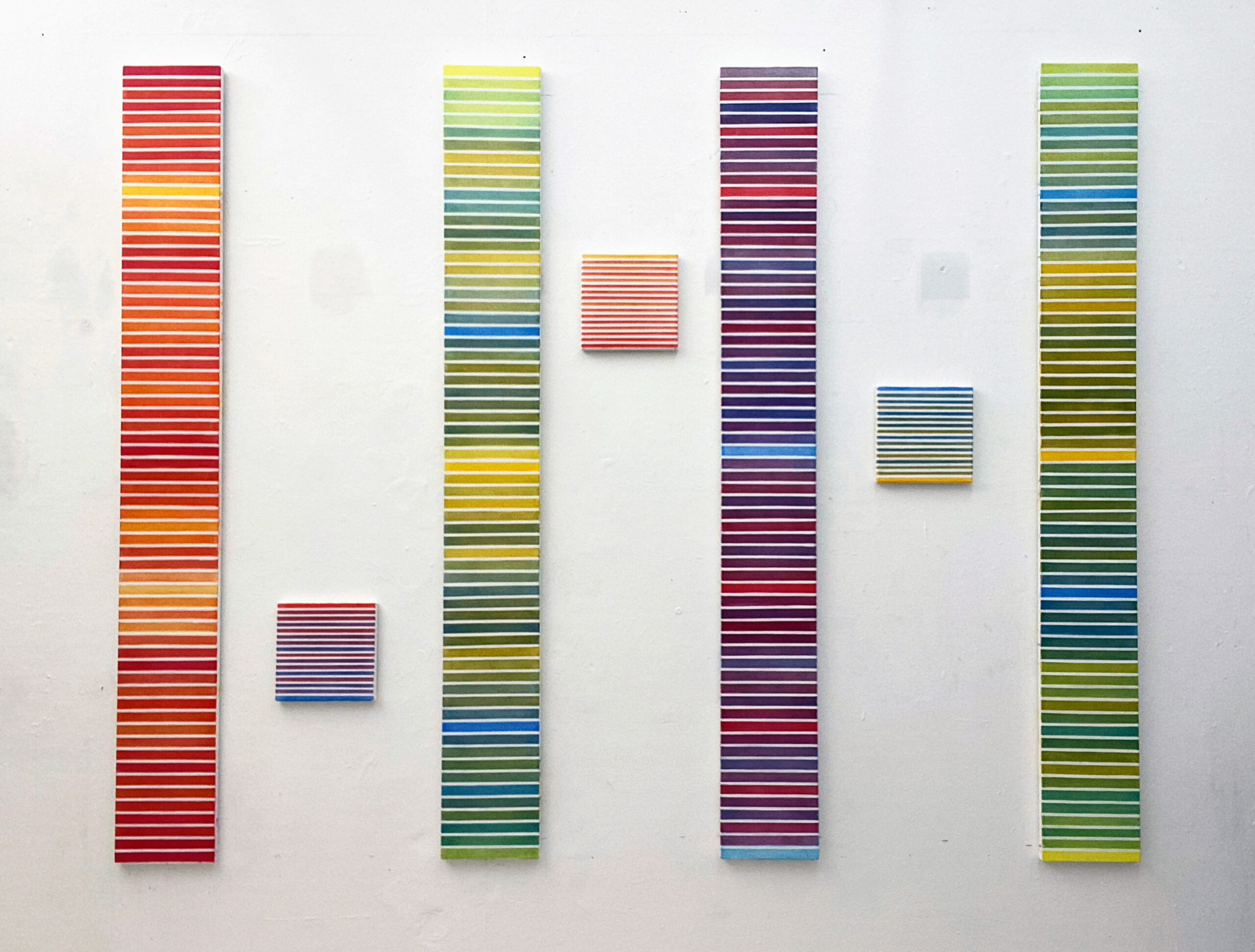

What do you like about your work

I like it when my paintings surprise. When I eventually stand back from them and see things in them had not anticipated. This is especially the case with my abstracts because the way in which I produce them means that I have no real idea of their appearance until I put them on the wall and stand back from them. As far as the labour of art making is concerned, I like its meditative, mindfulness, immersive aspects, and the slow thinking it induces. In the act of painting all external worries, anxieties and stresses dissipate; except, that is, when things go wrong, and you must exit this flow state to problem solve.

Should art be funded?

Yes, art should be funded and to an extent it is funded in the United Kingdom by the Arts Council England and National Lottery, amongst others.

What role does arts funding have?

Personally, I do not think public money should be used to fund the art market, although it is inevitable that some publicly funded work will eventually enter the art market. Instead, the role of arts funding ought to be to support the production and presentation of experimental art and practices that are presently, at least, noncommercial.

What is your dream project?

I recently visited the home and studio of the Victorian painter, sculptor and president of the Royal Academy, Alfred Lord Leighton’s, now the Leighton House Museum, which has recently undergone a major refurbishment that includes a wall painting by the Iranian artist, Shahrzad Ghaffari, that snakes up a spiral staircase. I presently prefer to work on a small scale, but Ghaffari’s mural has planted the seed of a project to work on a similar site-specific, public, and monumental scale.

Name three artists you’d like to be compared to.

My recent abstracts have been compared to Agnes Martin’s, which I find flattering as I was knocked out by her exhibition at Tate Modern in 2015, visiting it multiple times. I would be content to be compared to Mondrian, Cezanne, Gerhard Richter, or Bridget Riley, amongst others. I see all these artists, including Martin, as pursuing a line of inquiry and comparison would suggest that others recognize this in my abstract work too, even when the work is not visually like the artists named

Favourite or most inspirational place?

I am a Londoner living in Central London and perpetually inspired by what the city has to offer. Beyond London town, my second citty is Venice. Prior to the pandemic I visited the city at least once and often twice a year, including a month-long stay in 2016, and usually in the winter. The city is a miracle of invention, ingenuity, art, architecture, engineering, human audacity and confidence; it is utterly unique and always surprising, however much you think that you know it.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

My Head of School at Leicester was Albert Pountney, a sculptor and Rome Scholar who attended the British School in Rome between 1938 and 1939. He used to get very frustrated with students who were always thinking about what they were going to do rather than doing it. He would often bang one of his large thumbs down on a surface and bellow that the way of art was in the doing not the thinking. Although, Ideas are important in my practice, serving to establish an experimental framework in which I can work, Poutney’s advice reminds me of what is true for me, which is that it is making and the art that leads ideas not the other way around.

Professionally, what’s your goal?

To have more of my work taken into public collections. The Victoria and Albert Museum holds a collection of my computer art drawings, and the Tyne and Wear Archives holds a collection of watercolour portraits based on Victorian prisoner release photographs. For me, it is not about prestige but preservation and access. You know that for as long as these institutions exist your work will be preserved and available to public view.

Future plans?

Just to keep on making and exhibiting my work.